29 August 2007

Playing Yourself

David Hare has been in my study again. Not so much as a writer, but as a performer—or more accurately a writer moonlighting as a performer. In 1998 he became an actor—something he hadn’t attempted since he was a teenager. But performing his monologue Via Dolorosa proved a lot more difficult than he’d anticipated, and as a way of coping with the unfamiliar role, Hare kept a diary of the process: Acting Up. It’s an interesting read, not for the famous names he drops, but for the in depth way it explores the tension between the words you write on the page, and the words you speak in performance. What is the difference between acting and performance? And how do you play yourself?

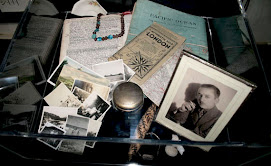

I was re-reading Acting Up as part of preparation for F.R.G.S. A 10-minute Performance Essay for the PowerPoint Age, and my contribution to 7-ON’s The Seven Needs. A piece I wrote for myself to perform; a piece in which I play myself. F.R.G.S. is my second Performance Essay, but the first to be learnt by heart rather than read. For me, this act of memory was the source of greatest anxiety: Yeah, I might be word perfect in my living room and in rehearsal, but what if out there in front of an audience …

Forever ago in London I played the clarinet and saxophone in bands, cabaret groups and fringe theatre companies, but it was obvious to me—and it certainly was to anyone who heard me—that I was never going to be the next Lester Young. So I started writing to escape my limitations as a performer. Now on stage again (fortunately this time minus musical instrument), the experience proved terrifying and empowering in just about equal measure. My sympathy for actors has increased tenfold!

I hit on the idea of these Performance Essays for a couple of reasons. One: I’d always been interested in the traditions of the illustrated lecture and ‘slide night’, and having written some pieces for ABC Radio Eye which mashed documentary, the personal essay and performance, I was interested in adapting that genre for live theatre, and two: I was looking for a solo performance form that would work for me as a writer, i.e. it had to be cheap, portable, and involve absolutely no funding applications whatsoever.

More on this later. In the meantime, back to David Hare and the art of public speaking.

12 August 2007

Representation-lite

With the publication of Lee Lewis’s Cross-racial Casting—Changing the Face of Australian Theatre, and an article about the issue in a recent Sydney Morning Herald, questions of representation are in the spotlight—again. This time the focus is on actors of non-European background, and their absence from main stages. Miss Saigon no doubt excepted. Anyway this flurry of interest got me thinking about representation more generally. An exchange in June in Theatre Notes, Back to regular programming … discussed this vexed issue in relation to gender. The dialogue sprang from an article in The Age about Joanna Murray-Smith, who had apparently written to the Sydney Theatre Company to ask why they weren’t programming her plays. Well, you've gotta admire her chutzpah ...

OK, here’s a view from Sydney on the STC: Yes, it certainly seems harder for a woman to get her foot in the door, even in the (relatively) small door of the variously-named Wharf 2 programs, where from Michael Gow in the early 1990s, to Brendan Cowell in 2007, the artistic directors have all been male. But why is the STC copping all the flack? Wasn’t it Belvoir Company B whose 2005 season included not a single female playwright or director? The perplexing thing there was that no one commented on this—at least not publicly. Does Company B’s strong record of supporting indigenous work buy them immunity from criticism on matters of gender?

Yes, women writers and directors are under-represented on our better-funded stages and over-represented in back rooms and pub basements. And many non-European performers struggle to get cast as anything other than gang members, refugees, and—for Asian actors—doctors. But I wonder how useful it is for us to keep chewing over this issue? Regurgitating essentially the same arguments? Plus ça change and all that. Perhaps in the words of Freedom, it’s time to ‘think outside the square’?

So here are a few thoughts:

· After a brief period in the spotlight, interest in inter-cultural work has waned. We still see overseas examples in festival programs, but for everyone here it seems it’s business as usual. Meaning artists from non-Anglo backgrounds get space to perform their own life-stories, but rarely a space to explore the questing, theatrically transformative agendas available to their White counterparts. (Why has interest in cross-cultural work declined? Would be interested to hear opinions about this … )

· It’s but a small step from representation to the heavy clay of identity politics, and escalating notions of ‘authenticity’. While I appreciate that autobiography and documentary are important genres in post-colonial societies, in that they are often the first places from which marginalised voices can speak and be heard … there’s a world beyond self-portraits.

· Is there really any point lobbying main-stage companies to represent our reality in anything other than a fairly tokenistic way, when they program for a conservative subscriber audience who, it seems, wants above all to see film and TV stars up close and personal? By all means send them your plays, and if they decide to produce them—fantastic. But if their door won’t budge, don’t waste too much energy trying to prise it open.

· Let’s remember that not all theatre writers and directors want to tailor their work and creative practices to fit main-stage imperatives. Sure, we’d like a share of their resources, but sometimes our artistic choices are better served in other contexts.

And finally—

Representation is too often posited as a destination rather than an ongoing process of engagement with the contemporary world. A destination reached through targeted initiatives and programs which can be rolled out like a carpet over any terrain, no matter how unsuitable or inhospitable. (I’m researching carpets at the moment, so they’re on my mind.)

Were these initiatives effective in the past? Maybe. To a degree. But the straight-talk about access and equality of opportunity that was once part of feminist, queer and post-colonial discourses of empowerment has given way as bureaucracies, universities and arts organisations have embraced the rhetoric. Today’s softer, more conciliatory calls for ‘representation’ have none of the rough edges of older demands for justice and transparency. So it should come as no surprise that what these well-meaning exercises produce is rarely any substantive or lasting engagement with diversity, but more often ‘representation-lite’.

OK, here’s a view from Sydney on the STC: Yes, it certainly seems harder for a woman to get her foot in the door, even in the (relatively) small door of the variously-named Wharf 2 programs, where from Michael Gow in the early 1990s, to Brendan Cowell in 2007, the artistic directors have all been male. But why is the STC copping all the flack? Wasn’t it Belvoir Company B whose 2005 season included not a single female playwright or director? The perplexing thing there was that no one commented on this—at least not publicly. Does Company B’s strong record of supporting indigenous work buy them immunity from criticism on matters of gender?

Yes, women writers and directors are under-represented on our better-funded stages and over-represented in back rooms and pub basements. And many non-European performers struggle to get cast as anything other than gang members, refugees, and—for Asian actors—doctors. But I wonder how useful it is for us to keep chewing over this issue? Regurgitating essentially the same arguments? Plus ça change and all that. Perhaps in the words of Freedom, it’s time to ‘think outside the square’?

So here are a few thoughts:

· After a brief period in the spotlight, interest in inter-cultural work has waned. We still see overseas examples in festival programs, but for everyone here it seems it’s business as usual. Meaning artists from non-Anglo backgrounds get space to perform their own life-stories, but rarely a space to explore the questing, theatrically transformative agendas available to their White counterparts. (Why has interest in cross-cultural work declined? Would be interested to hear opinions about this … )

· It’s but a small step from representation to the heavy clay of identity politics, and escalating notions of ‘authenticity’. While I appreciate that autobiography and documentary are important genres in post-colonial societies, in that they are often the first places from which marginalised voices can speak and be heard … there’s a world beyond self-portraits.

· Is there really any point lobbying main-stage companies to represent our reality in anything other than a fairly tokenistic way, when they program for a conservative subscriber audience who, it seems, wants above all to see film and TV stars up close and personal? By all means send them your plays, and if they decide to produce them—fantastic. But if their door won’t budge, don’t waste too much energy trying to prise it open.

· Let’s remember that not all theatre writers and directors want to tailor their work and creative practices to fit main-stage imperatives. Sure, we’d like a share of their resources, but sometimes our artistic choices are better served in other contexts.

And finally—

Representation is too often posited as a destination rather than an ongoing process of engagement with the contemporary world. A destination reached through targeted initiatives and programs which can be rolled out like a carpet over any terrain, no matter how unsuitable or inhospitable. (I’m researching carpets at the moment, so they’re on my mind.)

Were these initiatives effective in the past? Maybe. To a degree. But the straight-talk about access and equality of opportunity that was once part of feminist, queer and post-colonial discourses of empowerment has given way as bureaucracies, universities and arts organisations have embraced the rhetoric. Today’s softer, more conciliatory calls for ‘representation’ have none of the rough edges of older demands for justice and transparency. So it should come as no surprise that what these well-meaning exercises produce is rarely any substantive or lasting engagement with diversity, but more often ‘representation-lite’.

03 August 2007

Part of Being Australian is Feeling Part of Somewhere Else

2 things converged this week. At a 7-ON Playwrights meeting last Tuesday I learnt that the New Theatre in Sydney is celebrating its 75th anniversary with Art is a Weapon (the theatre’s original 1930’s slogan), and I started reading David Grossman’s Someone To Run With. These days I don’t read much literary fiction (far too many family secrets unravelling on windswept coastlines somewhere or other for my taste), but there’s a major dog in a new play that I’m writing, so I’ve been seeking out dogs in literature, and Someone To Run With features a stray Labrador. Anyway, browsing the Internet to locate a copy of this novel, and—thanks to the New Theatre—ruminating on the language-war nexus, I found this:

‘I once thought of teaching my son a private language, isolating him from the speaking world on purpose, lying to him from the moment of his birth so he would believe only in the language I gave him. And it would be a compassionate language … I wanted to take him by the hand and name everything he saw with words that would save him from the inevitable heartaches so that he wouldn’t be able to comprehend the existence of, for instance, war. Or that people kill, or that this red here is blood. It’s a kind of used-up idea, I know, but I love to imagine him crossing through life with an innocent trusting smile … the first truly enlightened child.’

That’s David Grossman, quoted in The Guardian, 16 August 2006. His son, who was in the Israeli army, had been killed a few days previously.

I’m not quite sure why, but Grossman’s plea, and the New Theatre’s resilience, both reminded me that a part of being an Australian is to feel a part of somewhere else.

‘I once thought of teaching my son a private language, isolating him from the speaking world on purpose, lying to him from the moment of his birth so he would believe only in the language I gave him. And it would be a compassionate language … I wanted to take him by the hand and name everything he saw with words that would save him from the inevitable heartaches so that he wouldn’t be able to comprehend the existence of, for instance, war. Or that people kill, or that this red here is blood. It’s a kind of used-up idea, I know, but I love to imagine him crossing through life with an innocent trusting smile … the first truly enlightened child.’

That’s David Grossman, quoted in The Guardian, 16 August 2006. His son, who was in the Israeli army, had been killed a few days previously.

I’m not quite sure why, but Grossman’s plea, and the New Theatre’s resilience, both reminded me that a part of being an Australian is to feel a part of somewhere else.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

+Photo+Leah+McGirr+3.jpg)