17 December 2009

Download Eels ...

17 November 2009

Dramaturgy & Dramaturgies #4

'Dramaturgies #4 will be a national gathering of artists and arts thinkers working over three intensive days to explore new ecologies for dramaturgical practice as we face the challenges posed by shifting theatrical forms in the twenty-first century. The gathering will include daily working groups to discuss specific questions of dramaturgical practice that require a detailed examination and response … '

Here’s what I’d ask: If hybridity is the destiny of our 21st century world—and I think the jury is still out on that, for every trend there is a counter-trend, etc., etc.—then what kinds of dramaturgical ideas and strategies do we need to develop for the modular script? For transcultural, bi-lingual and multi-lingual writing? To deal with open texts, site specific theatre and promenade pieces? With flash mobs, spoken word and the many and various forms of solo performance? With emerging music-theatre genres, with web-based, online and games-inspired forms? What happens to a story when mobile technology takes your writing outside the theatre space? How does the architecture of a place shape or subsume your narrative, determine characters, amplify voices, cast its shadow on the way you write? What happens when your ‘stage’ is full of unrehearsed passers-by, subject to inclement weather and random happenings?

Sounds like Dramaturgies #4 is going to address some of these issues.

For more info or to register your interest, go to their website: http://www.dramaturgies.net/.

15 November 2009

Enough with the 'Shoulds'

After a couple of false starts I decided that my old text would be Isaac Newton’s early notebooks, in particular his 1659 notebook with its colour recipes. Newton's interest in colour was enduring; he is famously the man who unwove the rainbow, and fractured light into its 7 constituent colours.

I got carried away, reading biographies, books about the history of colour, of calculus, of alchemy and astronomy. I carried out research in Cambridge and London during my stay in England. The only problem was, everything I read branched out into more possibilities, more tantalising leads to investigate. Which meant I arrived at a point where I had enough material and ideas for half a dozen scripts—but no clear story world for the one I’d been commissioned to write. This no doubt reveals something (perhaps rather too much?) about my writing process, but it’s a situation in which I often find myself. On the up-side however, I’ve found some of my best ideas while immersed in research for other projects.

I’m not, and never have been, a writer who plans out their script before they write it. I usually start with a collection of ideas, themes and metaphors. Sometimes with a musical form. Occasionally with a character or characters. Rarely with a detailed narrative. Never with plot. I begin writing to discover what it is I’m actually writing about. This time I began with 2 things. A form or style: I wanted to combine narrative and real-time dialogue, and a hazy sense of one character: I knew he was male, well into middle-age, and some kind of scientist. As points of departure go, this is loose and vague—even for me. So, not surprisingly, the writing has been stop-start.

All this is by way of a (long) preamble to explaining why I’ve read a lot of theatre reviews and blogs this last week. And been dismayed (and exasperated) by the overuse of one of my least favourite words: ‘Should’. Especially when directed at playwrights. Too many critics, bloggers, whoever and their dogs, telling playwrights how they should write and what their plays should do. Why do playwrights cop so much of this? No one seems to tell actors how they should act or designers what they should design to anything like the same degree. But it seems par for the course to bombard playwrights with ‘shoulds’.

Bit of an aside: why have we adopted this medical terminology of ‘script clinics’, ‘script doctors’, etc.? One London theatre company recently sent out a newsletter promoting their script clinic with a big red cross and the question: Is your writing practice in need of a check-up? What message does this give playwrights? All it does for me is conjure up the ridiculous image of a waiting room full of sick and bleeding plays.

Back to the ‘shoulds’. First reaction is that I’d like to tell those dispensing these pearls to stop telling us what we should do and write their own damn plays! A second, calmer, response is that question: why do playwrights get so much advice? Collective insecurity? The need to court those who program? Getting carried away by the collaborative nature of our work? Or perhaps it’s because, unlike say, playing the cello or performing somersaults on the trapeze, everyone feels they can write? Anyway, whatever the reason/s, I think a contributing factor is the notion of ‘rules’. Personally, when I hear the word ‘rules’ I run for the door. No, but seriously, the problem I have with ‘rules’ is (a). that they are predicated on the assumption that there is some universal notion of the perfect play, to which we all subscribe, (b). that ‘rules’ are not neutral and value-free, but derive from particular traditions and ideologies, and are answerable to certain interests (read the work of Trinh T. Minh-ha and Raúl Ruiz from the 1980s for more on this), and (c). despite what are no doubt the helpful intentions of many script gurus and dramaturgs, rules are often about control and gatekeeping as much as they are about the craft of theatre writing; any work perceived to be ‘breaking the rules’ can be safely shifted to the margins.

Of course this raises issues of dramaturgy, and a recurring preoccupation of mine: the relative lack of dramaturgical strategies and vocabulary for more experimental theatre writing, for work which is not primarily or essentially narrative drama, for work which is not about character arcs and plot progression. But now I’m starting to rant. Enough said.

BTW I’ve almost finished the first draft of Random Red. As for process here’s a favourite quote from Isaac Newton: ‘I keep the subject constantly before me and wait ’till the first dawnings open slowly, by little and little, into a full and clear light.’

06 November 2009

extempore 3

extempore 3 is out. The journal is edited by Miriam Zolin and this issue includes a bonus CD of contemporary Australian jazz, including a track by the wonderful Way Out West. Their 2002/3 CD Footscray Station remains one of my much-played favourites, and—directly and indirectly—has inspired performance texts, poems and spoken word pieces. You can also read my poem Learning (to love) the clarinet in this issue of extempore.

07 October 2009

Poetic Dialogue

Today I extended the cleaning jag to my computer and started deleting old emails. That’s when I came across a link to a 2007 article from The Guardian by Anthony Neilson. He’s basically telling playwrights not to be boring. No argument there. But this paragraph towards the end of the article caught my attention:

‘ … there’s a lot of poetic dialogue around. Sometimes a play is narratively accessible but the dialogue is mannered to the point of incomprehensibility. Some people like it, but I’m suspicious. Poetic dialogue, done badly, leaves no room for subtext. A lack of subtext is fundamentally undramatic. And boring.’

As a writer whose performance work is often described as ‘poetic’, my initial reaction to this statement was to disagree. I find naturalistic dialogue, when done badly, thin and pedestrian. It reduces theatre to work-a-day TV without the locations. Poetic dialogue can be subtle and work by suggestion and association; it can use metaphors to convey internal emotional states; it can sculpt language like designers use space or lighting designers compose with light; it can draw on and make manifest the inherent musicality of theatre.

Many years ago when workshopping Historia at an ANPC Conference, a dramaturg told me that actors find it hard to be emotional in non-naturalistic or poetic text. When he said that, I wanted to ask him: where does that leave Shakespeare? Not to mention those Jacobean dramatists I love like Webster, Middleton, Tourneur and Ford. Think of the candlelit and treacherous universe in which they moved, of sin unpunished, of innocence destroyed. Even the titles of their plays are strangely seductive, trapdoors to something beautiful and wicked that trickles beneath the surface of mortality: The Malcontents, The White Devil, The Broken Heart.

Since then, I’ve thought a lot about poetic dialogue, and I think Neilson’s got a point. Kind of. So here’s my riff on the pitfalls of the poetic in performance:

When a script gets labelled ‘poetic’ chances are its poetry and poetics won’t receive any further comment or critical input. This is unfortunate.

Poetry is a distilled, economical form of writing that can be many things—active, introspective, muscular, analytical, moving, funny, whimsical or robust. It can be direct and it can be plain in its syntax and metre. It can also be elusive. It requires discipline on the part of the playwright. It is not an excuse for a mud of adjectives, overblown description or a lack of dramatic action.

Whether I’m working on my own script or someone else’s, these are some of the questions I ask about the play’s poetics: Is the poetic lexicon sufficiently distinctive and varied? Or is it limited and predictable? Can it cut to the quick when it needs to, or does it circle aimlessly? Does it drift, or is it sharply focused? Does it invite the spectator into its world?

There’s more to say on the subject, of course, but I really should get back to that radio script. And to ‘keep myself on task’ here’s a favourite quote from Robert Wilson:

‘My ideal theatre would be a cross between the radio play and the silent movie. The problem with most theatre buildings for me is that they form a tight frame, the picture frame of the proscenium stage, which constricts and limits the fantasy. But when I listen to a radio play, I can look out the window and look at an airplane or a couple of lovers or the birds.’

01 September 2009

There's Something About Eels ...

The eel has an image problem. Koalas, giant pandas, dolphins, butterflies, kittens—some of nature’s creatures are Hallmark-cute and appealing. Others inspire respect and awe. But some—like the eel—make us shudder. A slippery fish that lurks in the mud of river beds, or coils up from the ocean floor to scare divers. But there’s much more to the eel than meets the eye. It’s an elusive creature, and a tasty one—eels are one of the human race’s survival foods. A creature with not only a remarkable life cycle, but also one with a long cultural history across cultures and continents. There's Something About Eels … combines science, literature, history, anecdote, reverie and culinary art in a radio portrait of this maligned, misunderstood and unusual creature.

29 July 2009

Dark Paradise

Jō and Ichiko Takasuka, Victoria 1914/5

DARK PARADISE is a radio piece, the story of Japanese immigrant, Jō Takasuka, who grew Australia’s first commercial rice crop in 1914/15—as told by a benshi or silent film narrator. From the moment the Takasuka family arrive in Melbourne in 1905, they have to battle not only a harsh physical environment, but also a hostile political climate, thanks to the notorious ‘White Australia’ policy. DARK PARADISE is a fictionalised account of such a time and place.

Written by Noëlle Janaczewska

Produced by Jane Ulman

Music: Chis Abrahams & Jim Denley

Performed by: Kuni Hashimoto, Linda Cropper, Asako Izawa

ABC Radio National: Airplay

Sunday 9 August, 3:00 pm, repeated Thursday 13 August, 7:00 pm, and available online for 4 weeks from first broadcast at www.abc.net.au/rn/airplay

23 July 2009

Noëlle on Another Lost Shark

14 July 2009

Minnie Mouse Redraws the Line

The piece is a playful speculation on the relationship between Mickey and Minnie Mouse of Walt Disney fame. Minnie finds herself under house arrest in a rundown hotel in Sydney. The studio suits at Disney want her to lie low for a while. Mickey is at the peak of his fame and the knowledge Minnie has of the 'real Mickey' risks a cartoon catastrophe.

Performed by Lucia Mastrantone. Produced by Libby Douglas.

11 July 2009

The Need for Imaginative Space

‘Writers are often asked, How do you write? With a wordprocessor? an electric typewriter? a quill? longhand? But the essential question is, “Have you found a space, that empty space, which should surround you when you write?” Into that space, which is like a form of listening, of attention, will come the words, the words your characters will speak, ideas—inspiration.

If a writer cannot find this space, then poems and stories may be stillborn.’

Read the rest of her lecture here.

15 June 2009

Cluster

Joanne, that probably describes how a lot of us feel—new, emerging, established, whatever …

11 May 2009

The City Lorikeets

30 April 2009

Savage Minds

A long time since I studied it, but I try to keep up with what's hot and what's not in anthropology.

It's not in any way about 'keeping my hand in', but it is more than idle curiosity, because anthropologists and anthropology-related themes have featured in a few of my radio scripts and plays, most notably Songket. And quite a few years ago I also wrote a couple of drafts of a novel in which 2 of the central characters were anthropologists. Very wisely, I binned that manuscript; decided to let it become ‘compost’ for other writings.

Anyway, this link has nothing to do with writing. It's a group blog on matters anthropological, it’s called Savage Minds, and I find it interesting reading.

19 April 2009

Playwrights, Directors, Auteurs ...

I’m a playwright, so of course I want space for writers to practise and develop their craft. Support for writers to initiate and develop their own ideas, as well as work on projects dreamt up by others. Opportunities to collaborate with different artists in the creation of work across the whole spectrum of theatre and performance. But what troubles me about Billington’s post is his notion of 2 discrete entities: a ‘writers’ theatre and a ‘directors’ theatre. And the implication that the rise of one presages the decline of the other. Isn’t it time we chucked this division in the bin? Isn’t it more useful to think instead of the whole ecology? Speaking for myself, I want to write for a range of forms, and work in a range of ways with a range of other artists. And maybe this is naïve or overly idealistic, but isn’t it far more likely that really good work in one area will encourage really good work in another, rather than jeopardise its existence?

This issue has particular currency for me as I’ve just returned from Melbourne and a week’s workshop with The Eleventh Hour on a new theatre project with the working title Debts. Drawing inspiration from Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, and from the various incarnations of Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin stories, including the film Cabaret, the project is looking at debt and notions of indebtedness. The concept is the brainchild of the company's artistic directors; as the writer, I am also contributing ideas (as well as text) and will help shape the piece; the actors likewise have input into the development of Debts. In other words, the work is collaborative, and is being created not solely by the playwright, not solely by a director or auteur, but by a team of artists with specific skills and roles. And isn't this the case with most theatre? Even if you sit in front of your computer and write a play with no involvement from anyone else, you're going to rely on collaborators to realise it as theatre, and unless you're a total control freak, those collaborators are going to participate in the creation of the work as theatre.

Last week's workshop was the first stage of our creative development, and I had a great week with directors/dramaturgs Anne Thompson and William Henderson, and actors Jane Nolan, Rodney Afif and Greg Ulfan. I’d contacted the company about 18 months ago, because I really liked what I'd read about them and thought they sounded like a company of substance rather than PR hype. (Which they are, by the way.) The invitation to collaborate on Debts came out of this initial dialogue.

Naturally we discussed our ideas for the piece around the table, but every day also involved plenty of work on the floor. Experimenting, trying out things, exploring possibilities, looking at what happens when you crash and juxtapose different texts, genres and styles. For a playwright this is fantastic, because I get to see how things might work theatrically—or not. It forces you to think performatively, of bodies in space, of words in mouths. It reminds you that sentences and situations that read brilliantly on the page may not be effective on stage; it encourages you to wrestle, question and rhapsodise. You bounce ideas around the room, off each other, and those ideas keep on bouncing around in your head as you board QF462 back to Sydney, as you do the weekend shopping, and days later as you walk along the foreshore at dusk.

2 more workshops/creative developments are scheduled for July and August.

03 April 2009

Wine & Cheese in the Amazon

France was at the top, then Italy, followed by Germany and Spain. Australia was at the bottom in a generic ‘New World’ category, with Chile off the list altogether because this was 1980 and Pinochet was in power. Like many people my age who grew up in England, wine was an exotic tipple associated with special occasions, continental holidays and bohemian proclivities. Although by the time I was at university, this was changing, and I could navigate the cheap shelves of the off-licence with confidence: Black Tower, Blue Nun, Bull’s Blood from Hungary, and Mateus Rosé from Portugal, which came in distinctive, bulb-shaped bottles to be recycled into lamp-stands and candle-holders.

Twenty-five-plus years later and 1,600 kilometres up the Amazon, I’m drinking Mateus Rosé again. And I’m not the only one: the ubiquitous pink is on the up again, benefiting from a recent surge in popularity of rosé wines.

‘Fondue & Wine Night’ at this particular restaurant in Manaus is a step back in time to that pre-cholesterol era when cheese was healthy and wine was sweet. It’s my last night in Manaus before I fly back to Rio de Janeiro, and I’ve come here because—well, a place advertising a ‘Fondue & Wine Night’ must have wine on offer. And with all that cheese to keep cool, I figure they’ll have that other essential: air conditioning.

Three degrees south of the Equator, Manaus is an oddity: a city of almost two million people in the heart of the Amazon. On the map it’s six boldface letters amid a swathe of green; on the ground, the humidity is crushing.

‘Because of the evaporation, Manaus is always evaporating,’ the taxi driver explained as he ferried me from the airport to my hotel.

Travel guides are not kind to Manaus, describing it as dirty and overcrowded, an oily blot on our rainforest fantasies. But I like the buzz and frontier ambience of this river port. I like the cast iron Municipal Market where biodiversity comes alive with tentacles and spiky rinds. The waterfront where porters run cases of guaraná and transformers to waiting barges. And the old district of Educandos, named after the teachers who were some of the city’s first migrants. Where one morning, I watched a businesswoman in high heels climb to her bus stop across a system of planks and makeshift bridges. And wondered why, despite housekeeping services and modern plumbing, I was sweaty and crumpled, while people living in the most basic of circumstances were immaculately turned out?

With this in mind, I’ve dressed up for the ‘Fondue & Wine Night’, applied lipstick, and taken a cab to the up-market Vieralves neighbourhood. But already my shirt looks as if I’ve slept in it.

From a few doors down, a band in full stampede. 2/4 syncopation loud enough to stagger the pulse of the neon sign across the street. Or maybe the power is about to short out, the way it did my second day here?

Around 4:00 pm branched lightening sprang from a black curve of the forest. Thick clouds, purple, grey and silver-edged, began to drop spots the size of tennis balls onto the path, and within seconds rain was pouring in sheets so opaque it was impossible to see the tree a couple of metres away—let alone the Amazon beyond. Straight down, taps turned on full capacity, the monsoon that swept in about the same time every day was especially intense that afternoon—my second in Manaus. The lamp in my room sparked, the fan stopped; there was nothing for it but to head for the lobby and a glass of chilled white wine.

That’s when I discovered the hotel bar didn’t serve wine. Only beer and spirits and a raft of soft drinks. The barman however, tried to oblige, rummaging under the counter until he found—

‘Red?’ he asked, holding up the remains of an unidentified bottle.

‘Uh—no. Thanks.’ I mean, God knows how long it’s been sitting there!

Later, in the café, I tried again.

‘Sorry, no wine. Would you like a Coke instead?’

I could, I discovered, order a bottle of wine on room service. There’s Local or Imported. Imported from where? France, Chile … Uzbekistan? I called to ask.

‘From overseas, madam.’

I opted for the local white.

Ten minutes later, a waiter arrived with a tray and two glasses. Only to hesitate, confusion crinkling his brow, reluctant to open the bottle for a single senhora.

Is this the lot of the solo traveller? Or is it a wine and gender thing? ‘[T]he assumption on the part of wine waiters that women are too frail to consume or too stingy to pay for a whole bottle,’ as Elizabeth David put it. Whatever the case, I ended up pouring most of that room service Chardonnay down the sink. Not because it was unpleasant, but because I realised with the first sip, that what I really wanted, was to enjoy the drink of my choice in a public space.

Like its cuisine, the décor at the fondue restaurant is pure 1970s. In fact much of Manaus’s appeal is retro—not reconstituted heritage, but the real 70s deal. Take concrete. Like their colleagues elsewhere, the architects of modern Manaus embraced concrete with a vengeance, and everywhere you go, there it is: smooth concrete, bumpy concrete, windowless concrete, textured, moulded, weed-sprouting concrete. Is it an aesthetic choice? Or an attempt to combat the weather, the decay that creeps up every façade and pillar, the moisture that softens everything?

Manaus is a boom and slump sort of place, and if the concrete jungle is the design legacy of the boom that began in 1966 when the government declared the city a free-trade zone, then the pink and white opera house is the most visible reminder of that earlier boom, what translator Leandro calls ‘the rubber time’.

‘Everyone,’ he announced the first time we met, ‘has a certain size to their life, and you can refuse to fill it or use it all.’

A philosophically-inclined man with indigenous bone-structure and expressive hands, Leandro talked with affection of Eduardo Gonçalves Ribeiro. State governor during the final decades of the nineteenth century, his flamboyant determination to bring ‘light into the dark forest’ was a source of inspiration for Werner Herzog’s 1982 film Fitzcarraldo. Ribeiro’s tenure coincided with the rubber boom. A period of monopoly when entrepreneurs and bosses lived in outlandish luxury. When Camembert and raspberry jam arrived on steamships from North America; when horses were given vintage Burgundy to quench their thirst, linen sent to Paris or London to be washed, and ladies donned gloves and fur coats to hear Verdi’s latest at the newly-opened Teatro Amazonas. Although, as I sat in that theatre, in my red velvet seat, listening to a string quartet rehearse, I wondered about the truth of these stories, which seem to become more baroque with each retelling.

We were outside the theatre, taking photographs, when a boy appeared at the top of the steps. He was about ten or eleven-years-old, barefoot, pushing a battered wheelbarrow full of pineapples. Another vendor attempted to shoo him away; trade in tourist hot spots is strictly controlled. The pair of them yelled insults at each other, until the vendor marched up to the barrow and kicked it over. Wheelbarrow and pineapples tumbled down the steps, but Eisenstein wasn’t there to record for posterity that image of falling fruit. Or the dignity of the boy as he picked up his livelihood.

‘He’s probably left the interior for the future,’ explained Patrícia, an architect from São Paulo, here as part of a scheme to provide in-town housing for the region’s native peoples. Housing that will acknowledge their traditions whilst accepting the fact that they are now urban dwellers.

Buy a Nokia phone in Recife or a Samsung TV in Porto Alegre, and chances are it was put together in Manaus. Drawn by the promise of tax relief, multinationals moved into the Distrito Industrial, and at night you can see their corporate logos lording it over the city. The aristocrats of this second boom are executives from Europe and South Korea, but unlike their predecessors, the majority of them will never actually set foot in Manaus. As for the workers, many of them hail from remote communities off the radar for all but the most intrepid anthropologist.

By now I’d given up looking for wine by the glass or half-carafe in favour of a bottle of anything I could imbibe in a public venue, rather than alone in my room. A quest that took me to the poolside buffet of a nearby hotel.

‘Can I see the wine list?’

The waiter handed me the standard menu: cocktails, spirits, beer and non-alcoholic options. I repeated my request, this time in Portuguese. He sighed and made for the waiters’ station. Surely I’m not the only wine-drinker in Manaus?

The list when it arrived, was short and predominantly Argentinean. ‘I’d like the Brazilian Riesling, please.’

‘Blanco ou tinto?’

I don’t think Rieslings come in red, do they?

A bottle of Marcus James was brought in an ice bucket to my table by another waiter, a stocky, older man, his face overgrown with fatigue. It turned out to be a rather bland, thin-bodied drop—No, let’s be generous and call it ‘refreshing’. Besides, after all that hunting, I was determined to enjoy it.

Wine grapes were introduced into Brazil by the Portuguese as far back as 1532, but encountered various environmental problems and failed to flourish. As did the Spanish vines planted by Jesuit missionaries along the Uruguay River a hundred-and-thirty years later. It was not until the 1880s that Brazilian viticulture got going in the southernmost state of Rio Grande do Sol, thanks to the know-how and persistence of Italian immigrants. Wine grapes are now also grown in north-eastern Brazil, and the upper São Francisco valley is probably the most important tropical vineyard in the world. This would certainly surprise the Victorian explorer Richard Burton, who visited the area in 1867 and wrote: ‘Grape growing will hardly be possible in this climate, where the hot season is also that of the rains.’ But a hundred-and-fifty years after Burton, this scrubland of stunted trees and prolonged droughts is producing millions of litres of wine. The vines depend on irrigation for survival, and on restricted fecundity for quality control. Doubts remain however, about the wisdom of the enterprise; the suitability of grapes from tropical climates to produce anything more than vinho de mesa or vinegar. What isn’t disputed, is that each hectare of cultivation provides much-needed employment in this desperately poor part of Brazil.

In contrast to the wine drought, I’ve never in my life been offered so much cheese. Or to be strictly accurate, so much gorgonzola. It’s there for breakfast, there for lunch on pizzas and pasta; it’s dug into mashed potato, stuffed into fish, even disguised as soup. Tourist agencies could use it on billboards to promote the town: Want to gorge on gorgonzola? Come to Manaus!

In a satirical essay, G. K. Chesterton observed that poets have been curiously silent on the subject of cheese. Not so the contributors to Wikipedia, where cheese is apparently one of the on-line encyclopaedia’s most reworked topics—along with Fidel Castro, deconstructivism and Israel. I recognise the controversial nature of the other entries, but why does cheese inspire such passion? Myself, I regard cheese as politically neutral, although there is that pre-gourmet association with parsimony and spinsterhood, captured so succinctly by Barbara Pym: ‘I went upstairs to my flat to eat a melancholy lunch. A dried-up scrap of cheese, a few lettuce leaves … A woman’s meal, I thought, with no suggestion of brandy afterwards.’

Today, my last in Manaus, I hired a driver and went to the Adolpho Ducke Reserve and Botanic Gardens on the eastern outskirts of town.

‘Not long ago you saw only the forest from out here,’ said Amir, as he parked the car. ‘Now look! Skyscrapers and buildings.’

I couldn’t tell if Amir regretted this change or welcomed it, but not much more than twenty kilometres from the traffic snarls and Internet cafés of Centro, the road ran out. Literally. You’re in the middle of nowhere with forest in every direction. Amir turned off the engine, and a heavy press of silence descended. Was it only a few minutes ago that we passed gardens cut out of the bush? A makeshift church? Huts selling cachaça and cans of Coca-Cola, clothes drying on wire fences?

When the military took over in 1964, national security became a government priority, and the Transamazônica Highway was designed to link the Atlantic coast with the Peruvian border. A grandiose project in the Fitzcarraldo mould, the motorway remains unfinished. Of the 2,500 kilometres so far constructed, much of it is unpaved, making it not only impassable in the rainy season, but also prone to reinvasion by the forest.

Except for the road to Boa Vista, 450 kilometres to the north, Manaus has no sealed roads linking it to any other city.

‘Do you ever feel isolated?’ I asked Amir.

He was puzzled by the question.

I explained that I once spent several months in Perth on the edge of Western Australia. Often referred to as the most geographically isolated city in the world, I was aware of its remoteness, the desert breath of the Nullarbor on the back of my neck, the whole time I was there.

Amir shook his head. Manaus is different. ‘Because of the river.’

As we were leaving the Reserve, I spotted a kid in a Star Trek T-shirt kicking a football back and forth across a dirt track pockmarked with puddles. This was indeed the final frontier, and at least by road, there was nowhere else to go—boldly or otherwise.

‘May I have the bill, please?’

The head waiter darts over. Is everything is all right?

The food was fine, the service prompt, the wine—well, there’s only so much ‘blush’ or rosé a girl can take, despite new packaging and ad campaigns aimed at encouraging us to ‘Drink Pink’. When I was a student we drank Mateus Rosé because it was cheap. Perhaps for today’s twenty-somethings, it is their way of rebelling against their parents’ tastes?

Outside the restaurant, the street crackles with anticipation, diesel fumes and barbecuing fish; crowds throng open-air bars pumping out competing rhythms, and impeccably dressed couples saunter along, seemingly impervious to the evening drizzle. I feel scruffy and unironed again, but I am starting to understand something about those rubber barons and their laundry.

When I get back to the hotel, I grab a big, golf umbrella and sit for a while on the wall behind the car park. The Amazon on that last rainy night offers no horizon, rolling unbroken into a wet, inky infinity. Sky and river in unison. Miles out, I can see the silhouettes of tiny boats as they bob among the churning water, like dragons on a medieval map.

‘Quando ele volta?’

Suddenly, behind me, a loud voice. A businessman paces up and down, shouting into his mobile. A snake slithers between two vehicles and into the garden. The man’s foot misses it by inches, but he’s too engrossed in his phone conversation to notice. Or too blasé. To be familiar with a place is, after all, to be blind to the strangeness it presents to outsiders.

24 March 2009

Writing about Milwaukee

Downtown Milwaukee

Jones Island, Milwaukee

Those old industrial towns and cities have a particular geography and civic architecture that remind us of the forgotten social contract between the ‘brotherhood’ of workers and the company bosses.

18 March 2009

Writing Matters

‘ … in many ways, I think what playwrights do is more important than what most politicians do. Being a dramatist isn't just about writing. That part often takes just a few weeks. But we do spend a long time thinking about how people behave, how they live together, how they might live together better—as well as the great cruelties they are capable of. And we're constantly testing language, time and space in our work, to extend the possibilities of human experience. Politicians are concerned with the pragmatic business of running the world; artists, meanwhile, dedicate themselves to finding new insights into our existence. Most of the insights are feeble or crackpot—but some are visionary.’

Read the rest of Mark Ravenhill’s piece here.

In the meantime, as I begin to formulate my 7-ON Old Texts Revisited project, I'm thinking about Australian history. Having neither grown up here, nor gone to school here, my ignorance of this subject is admittedly vast, but there's got to be more to it than a chronology of important men and portraits of men at war—surely? So how about adding a bit more of the female experience to the picture? And let's think past the predictable (prostitutes and gangsters’ molls). What about the domestic workers, the shop girls, the milliners, the midwives, the music teachers, the post office clerks, librarians, hospital cleaners, social activists, florists and baby-sitters, the back-street abortionists, book-keepers, barmaids … ?

10 March 2009

Excerpts x 2 from Eyewitness Blues

Fifty-something jazz musician, Jac, and 15-year-old schoolgirl, Gia Nghi, both witness a botched robbery at an outer suburban 7-Eleven. Their statements to the police however, reveal more about themselves than the crime.

Excerpt 1:

JAC

The loan that built the house for me and the ex, wasn’t big enough to buy the paint or plant the garden, so I took a second job. For extra money. To put down roots.

Pig Face, Acacias, Native Fuchsias. Not that you’d know that to look at it now. Wind-blown rubbish and dandelion clocks, more like.

But nothing took, no water-wise plants, no family, no tree.

And she’d say: I never see you these days.

And I’d say: It’s only temporary. Til we get on our feet.

And then she was gone, along with the kids, leaving me alone with the desert and the Camels …

Excerpt 2:

Excerpt 2:

GIA NGHI

Sometimes, the wind off the desert makes it hard to swallow.

Over there’s where you get the bus to the city, and that way—nothing. Few kilometres north, the land crumbles to desert. It used to be under the sea or a lake or something. Before it dried up and went salty.

Sometimes, at night, I imagine the extinct animals in a sort of reverse Noah’s ark. Leaving 2 by 2, through a door in the back of the world.

Or the camel on the cigarette packet walking off in search of water.

Ghosts have trouble with water, my Gran says. I reckon Australia must be ghost paradise then. Because it’s so dry.

26 February 2009

Procrastination

Procrastination. Something I know intimately, as I suspect do many other writers. Although I’ve come to accept it as an integral—and perhaps necessary—part of the creative process, I still often berate myself for wasting time and not getting on with the task at hand. Since reading this delicious essay How to Procrastinate Like Leonardo da Vinci by W A Pannapacker, however, I’ve decided to stop with the scolding and embrace my “inner procrastinator”, because ‘Leonardo, it seems, was a hopeless procrastinator ... ’ and who am I to argue with Leonardo?

‘Of course, the therapeutic interpretation of Leonardo—and, perhaps, of many of us in academe who emulate his pattern of seemingly non-productive creativity—has a long history. Leonardo’s reputation spread at exactly the right time for someone to become a symbol of this newly invented moral and psychological disorder: procrastination, a word that sounds just a little too much like what Victorian moralists used to call “self-abuse.”

The unambiguously negative idea of procrastination seems unique to the Western world; that is, to Europeans and the places they have colonized in the last 500 years or so. It is a reflection of several historical processes in the years after the discovery of the New World: the Protestant Reformation, the spread of capitalist economics, the Industrial Revolution, the rise of the middle classes, and the growth of the nation-state. As any etymologist will tell you, words are battlegrounds for contending historical processes, and dictionaries are among the best chronicles of those struggles … ’

Read the rest of W A Pannapacker’s article on the Arts & Letters Daily website.

22 February 2009

The View From There

The View From Here is a collaboration between London’s Slade School of Fine Art, the Bartlett School of Architecture and the BBC. It explores notions of cultural translation and trans-positioning by artists working in different media, drawing from the 3 key project terms: transmit, translate, transmute.

For Transmit 4 visual artists, from Australia, China, Israel and Uganda, each filmed a 12-minute video in a locale connected to their work, under the title The View From Here. These works were then sent to a writer in the artist's country to author a radio drama inspired by it. These 12-minute dramas have been recorded for broadcast on the BBC World Service on 28 February 2009 in the final stage of the project. The artists are: Barbara Bolt (Australia), Xioapeng Huang (China), Shuli Nachshon (Israel), and Daudi Karungi (Uganda). The writers are: Noëlle Janaczewska (Australia), Dinos Chapman & Simon Wu (Hong Kong/UK), Katie Hims (Israel/UK) and Charles Mulekwa (Uganda).

Translate: Eleven PhD students from the Slade and Bartlett made a series of works, in response to either those 4 works or the theme. The works will further inspire other students, invited to the event as respondents, to reshape, translate, transpose the original works through a text/image/audio/performance piece of their own.

Transmute is a combination of a BBC Broadcast and a Live Event on the 27 February. This final event will combine the broadcast, the original films and the resulting re-interpretations.

It's all happening at the Slade Research Centre, Woburn Square, London WC1.

08 February 2009

Watching the Lorikeets

Ferdinand Bauer: Rainbow Lorikeets, 1802

I knew absolutely nothing about rainbow lorikeets when they first caught my attention, but after a couple of trips to the library, a few book purchases, and a lot of looking, I'm a lot better informed—not only about lorikeets, but the parrot family more generally. This research has led me into some interesting areas and, as random, freewheeling research so often does, it's also given me ideas, stories, and material for other projects. One of which is a 7-ON commission for ABC Radio National. We've all been asked to write a half-hour radio script on the theme Old Texts Revisited. We can interpret 'texts' broadly, the only proviso being whatever text/s we chose to work with must predate the invention of radio. Being obsessed with maps, I was intending to look to cartography to supply my 'text', but now, thanks to these birds, I'm going to use something quite different.

30 January 2009

australianplays.org

26 January 2009

From Taishō Chick

Here's that excerpt from Taishō Chick:

…

In times of change I open the dictionary.

Not literally, but to open a crease in the language and reveal what we couldn’t say yesterday

in public

we drummed out syncopated rhythms with chopsticks. Drew cartoons with cold coffee on table tops.

Painting was my way of walking into the heart of the world without anybody knowing I was shy.

A taxi over the bridge, a little avant-garde introspection in the shade of the willow trees, and rice riots—that’s rice, R-I-C-E, not race. The poor were being bossed around by the high cost of rice.

For the not-so-poor

It was the age of silk stockings, foxtrots and all that jazz.

Of department stores and opinions—remember, long before the iPod brought music to our ears, the I-novel brought us first-person narratives.

I look for myself

and find

a café waitress lining up her future. Irie Takako starting her own film production company. Journalists reporting the latest from Paris or Shanghai. Young men in suits tailored British style.

And the key to all this activity?

The city.

The adventures and affairs of the metropolis …

18 January 2009

Guerrilla Gardens

Pyrmont is an inner city suburb of apartments and recent redevelopment a hop, skip and jump from the Sydney CBD. Many of us live in units with garden areas shared by the whole building. Gardens designed and laid out when our blocks of flats were constructed, and thereafter maintained by contractors. So it does more than jazz up my walks around the neighbourhood to discover that local residents have dug up verges and sections of public space to plant rosemary and rocket. Or apartment dwellers reclaimed their manicured borders and sown lettuces between the body corporate's shrubs.

Didn't realise it when I began taking an interest in the Pyrmont plots, but guerrilla gardening is a growing urban phenomenon. According to Wikipedia it’s ‘political gardening, a form of non-violent direct action, primarily practiced by environmentalists.’ But from a quick online trawl the term seems more of an umbrella one to describe different kinds of community gardening, with differing mixes of social and horticultural ambition. (Guerrilla Gardeners is also the title of a forthcoming Channel 10 program. Haven’t seen it, but here's how I’d guess it goes: instead of feral kids, wayward pets or ailing back yards, a photogenic, predominantly blonde team makeover scrappy public places. Lifestyle activism or protest lite for a primetime audience. But hey, maybe for once those TV executives will surprise us … ?)

Anyway, the guerrilla gardeners of Pyrmont have sparked my curiosity, and I'm going to keep my eye on their plots—who knows, I might even join them for a spot of midnight night spade work? In the meantime, check out GuerrillaGardening.org

10 January 2009

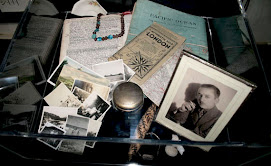

The Hannah First Collection, 1919—1949

A performance essay with PowerPoint images and a display case of ‘memorabilia’ we presented The Hannah First Collection, 1919—1949 as part of the Zendai Museum of Modern Art's Intrude: Art & Life 366 project in Shanghai in November 2008.

The work charts my quest to discover and reconstruct the life and journeys of the early-to-mid 20th century anthropologist and traveller, Hannah First. Drawing on the traditions of the old-fashioned ‘family slide evening’ and the ‘illustrated lecture’ as well as the blog and social networking sites, I follow Hannah from Amsterdam to Oxford. Check out her trips to Ceylon and Singapore, and her fieldwork in Central Europe, Palestine and the palm-fringed Tikabar Islands of the Western Pacific. To do this, I use not only photographs, notebooks and artefacts, but also my own life experiences—finding considerable symmetry between myself and this intriguing and improbable anthropologist …

In the last part of the performance, following an important revelation about Hannah First, I move on to explore our preoccupation with nostalgia. Why has nostalgia become our preferred mode of reckoning not only with the present, but with a strangely depoliticised past?

Conceived, written & performed by Noëlle JanaczewskaDirected by Sally Sussman

In Shanghai we presented a bilingual version of The Hannah First Collection, 1919—1949, in English and Chinese.

Chinese translation: Wu Chenyun

Chinese performer: Yao Mingde

This project was supported by the Australia-China Council.

01 January 2009

Time To Refocus

Well, that was the theory. The practice was that last year I posted a mere 4 times. There are a lot of reasons I can give for this: lack of time, pressure of deadlines, the imperatives of paid work (doing it and looking for more), other commitments, the ups and downs of the freelance life, perfectionist tendencies … the usual suspects. To which I’d also add: the wrong direction—for some reason I’ve ended up focusing too much on arts issues and policies—and the death of my father.

My father died in September, and I’m still grieving. He taught me to value the life of the mind, to love questions more than answers, and the quest more than the goal. He put the wanderlust in my soul and didn’t complain when it took me to the other side of the world. And he had a talent for spinning stories out of the mundane, and infusing even a simple stroll with a sense of mystery. I remember one night when I was still at primary school, Dad woke us up, myself and my brother, to go for a walk to see a badger set and listen to the call of owls. The badgers proved elusive, but the owls were in fine voice. Reflecting on that incident now, I realise it was probably not terribly late at all, but as a 7 or 8-year-old, it felt as if I were being woken in the middle of the night to go on a magnificent adventure.

Me & Dad

In the days immediately after my father’s death I wrote like crazy. On the long flight from Sydney to London I used my laptop, and when its battery ran out I continued writing with pen and paper. After the funeral however, the words ran out and my mind fixed on questions of time—time being finite, time running out, how I wanted to spend my time ...

3 months later, this is where I’m up to:

- I might have a lot of opinions, but an opinion column is not what I want to spend my time writing. (There are others more engaged with and better placed to critique arts issues than I am.)

- I don’t need another unpaid writing gig.

- If time spent blogging is time I could be writing other things, then why not use the blog as more of a writer’s notebook?

So I’m going to use this blog somewhat differently. I’m relaunching it in a looser, more flexible vein. It will be more of a notebook, there for process, a place of personal reflection, a place to jot down snippets and random ideas or start new trains of thought. I may post excerpts, report news and comment on work that I have seen, heard or read—and I may not. I will post as often or as infrequently as I wish and give myself the latitude to look outside theatre and write about whatever sparks my interest.

For example, in March 2008 I saw an exhibition of photographs at the National Maritime Museum: Steel Beach—Shipbreaking in Bangladesh. I’ve long been fascinated by certain kinds of documentary photography—Sebastião Selgado, et al. And these photos of a huge, muddy ships’ graveyard in the Bay of Bengal by Andrew Bell completely captured my imagination. I wanted to write about them, not a review, but a more personal, poetic kind of response to his images. I didn’t—for a whole bunch of reasons, not least because: where would I place something like that? So I’m going to use the new, realigned outlier-nj for things like that.

Another ongoing interest is architecture and urban geography—reignited in November when I went to Shanghai to present The Hannah First Collection, 1919—1949 as part of the Zendai Museum of Modern Art’s Intrude: Art & Life 366 project. Zendai MoMA is in the Pudong district of Shanghai, so that was where we were staying. In his book Concrete Reveries, Mark Kingwell describes Pudong as an area of ‘shopaholic emptiness’. True—to a point. But my stay there got me thinking, and now researching and writing, about skyscrapers and the migration of the early 20th century American skyline to other parts of the world. Not sure yet what form this piece will take—will keep you posted.

So what else for 2009? As well as projects with 7-ON, I’m concentrating on the Performance Essays. I hope to find a venue/context to present The Hannah First Collection, 1919—1949 in Australia, and I’m writing Bounce, a new performance essay about the history of rubber and how I wanted to be an explorer when I grew up. About my recent trip to the Amazon and my father’s journey through Parkinson’s Disease to the great unknown of death. Oh and I’m also branching out with projects across non-fiction, fiction, spoken word and poetry.

Happy 2009!

+Photo+Leah+McGirr+3.jpg)