19 December 2007

The Development Sceptic

Like American playwright Richard Nelson, from whom that quote comes, I’m a development sceptic.

Last week I received a request to complete a survey about script assessment, and it got me thinking about those sectors of the theatre industry dedicated to ‘script development’. Are they really about getting more and better new performance scripts into production, or are they about exactly the opposite?

I’ll come back to this topic in a later post, but in the meantime, here’s the text of Richard Nelson’s 2007 Laura Pels Foundation keynote address, which asks: Why do playwrights’ need so much ‘help’?

18 November 2007

Why Do Some Ideas Last the Distance, and Others Don't?

But aside from worrying about deadlines, what’s been occupying my thoughts this week is the question of why some ideas endure, while others have limited longevity. What does an idea have to have, what kind of idea does it have to be, to sustain my long-term interest? Is it a matter of topicality? No, I don’t think so, although obviously the issue going off the boil, (or conversely heating up so much that it’s the subject of every second play) can contribute to waning enthusiasm. Is it about the length of time between concept and theatrical realisation? Well, that can be a factor, but it doesn’t explain why some ideas capture my imagination and refuse to let go, while others are what I call ‘firework ideas’.

I have this theory that it’s always the project ‘2 projects away’ that is the most attractive and exciting. Not the next one, getting closer by the day to the moment when you’re going to have to knuckle down and do the hard slog, and definitely not the current one. No, it’s the one after the next one which is so enticing. Still open and brimming with possibility …

Time to go and pack. I think I’m going to have to come back to this question of why some ideas persist. Perhaps when my brain isn’t cluttered up with things like travel insurance and trying to find those gloves I bought last time I was in a Northern Hemispher winter. In the meantime, here’s an interesting article On Myth by Marina Warner, which looks at the staying power and elasticity of myths. It also reminded me to reread one of my favourite books: The Book of Imaginary Beings by Jorge Luis Borges.

26 October 2007

Artistic Downshifting

The debate about ‘doing it yourself’ or ‘artistic downshifting’ in the words of writer and film-maker Kathryn Millard, goes on. As technological developments create new platforms and possibilities, and government funding becomes scarcer and more prescriptive, there’s a lot to be said for writing outside the system. A couple of years ago I spent several weeks writing applications, several weeks hard-chiselling round pegs to fit into funding bodies’ boxes. Only afterwards did I wonder about all the time spent filling out forms, composing punchy synopses, and justifying processes; time I would otherwise have spent writing a script or an essay, a story or poem—something real, and useful.

26 September 2007

Postcard from OzAsia

In the last few years the favoured argument seems to be that a robust arts community increases the ‘liveability’ of a city or state, increasing its attractiveness for business investment, thereby providing jobs, et cetera, et cetera. What concerns me is not so much the truth or otherwise of these assertions, but the fact that we’ve jettisoned the language of culture and aesthetics in favour of the language of economic-impact studies—the language of politicians, in other words. And I think this concession, this shift to economic rather than cultural argument, is dangerous.

It’s dangerous because—thanks to widespread cultural illiteracy and a largely debasing mass media—most Australians have no idea why public support for the arts is worthwhile. So even though politicians tell us we’re living in an era of unprecedented (material) prosperity, the arts are starved of vital subsidy, and arts education is sidelined as irrelevant to the New World Economy. Then in a stroke of Orwellian cunning, that lack of appreciation is used as a rationale to continue not funding the arts.

Back to OzAsia, an excellent and much needed initiative, putting a bit of cultural diversity back onto the arts table. A table which—after a brief 1980s/early 90s flirtation with rye and pitta and Vietnamese pork rolls—has reverted to white sliced. (Although I must admit that when I read clunky sentences like: ‘Australian artists that identify with an Asian heritage’ various bells start ringing.) The symposium brought together practitioners, academics, arts administrators and representatives from a range of funding and state and federal organisations. So saying … when governments use the arts to spearhead trade programs or diplomatic initiatives, what companies and kinds of work do they chose to sponsor? Large dance companies, classical music ensembles, circuses? Productions guaranteed to make a big splash. But what about that small group of independent artists developing a more risky or experimental project, or beginning a long-term collaboration? Thank goodness then for Asialink, who seem to understand that professional relationships are built slowly, and that good work, especially that which crosses the boundaries of language and geography, takes time as well as resources.

The highlight of the symposium for me was undoubtedly the keynote paper from Calcutta-based writer, theatre director, cultural critic and independent scholar, Rustom Bharucha. It’s difficult to summarise because of the wide range and complexity of the issues he addressed. But here goes … Drawing on his 2006 book Another Asia, he exposed the capitalist bones of this hugely heterogeneous body called ‘Asia’, queried the word ‘enmeshment’, explored issues of nationalism, exchange, creative process, community, intercultural dreaming—and much, much more. It was passionate and provocative, eloquent and erudite, and I only wish there had been more time to discuss some of the ideas he raised.

Seems appropriate then to end with this favourite quote from Edward Albee: ‘Theatre tells us who we are, and the health of the theatre is determined by how much we want to know.’

18 September 2007

Writing Korea & Questions of Connection

Also reconnecting with the plugged-in world of the South. Remembering for some reason, the omnipresent fatigue: In a Seoul café a 40-something man nods off, his coffee going cold on the table in front of him. Sprawled on nearby benches, students take a nap. While on the subway, I’d often find myself the only person in the carriage who was awake. Remembering too those conversations I had with people about traditional culture and globalisation. A recollection prompted, I suspect, by reading Nayan Chanda’s Bound Together: How Traders, Preachers, Adventurers, and Warriors Shaped Globalization, which offers more than the usual economic perspectives on this topic.

Anyway, getting ready to present UNREQUITED at the forthcoming OzAsia Festival in Adelaide, I’ve been thinking about questions of tradition, authenticity and that oft-repeated mantra: art is a universal language. Here’s where I’m up to:

Cultural traditions are porous; authenticity, like El Dorado, is a myth. For any tradition to thrive, the old and the new need to engage in a dialogue with each other. And it goes without saying that what constitutes tradition can be difficult to gauge, and even more difficult to agree upon.

I wouldn’t deny the power of art as a universal language, but would suggest that it’s a more complex contention. For example, the only time I can honestly say that I’ve ever connected with Ibsen, was through a production of A Doll’s House performed entirely in Bengali. I’ve lived happily through King Lear in Korean, and a Vietnamese adaptation of the Albert Camus play Le Malentendu gave me real insight not only into local issues specific to Hanoi at the time of the production, but also into the original 1944 context of the work. In all these cases however, what was transmitted were the storylines, themes and moral dilemmas the playwrights wished to communicate, not their manner of conveying it. So I’d venture that substance is what makes art universal; style places it distinctively, and uniquely, in its own culture.

29 August 2007

Playing Yourself

David Hare has been in my study again. Not so much as a writer, but as a performer—or more accurately a writer moonlighting as a performer. In 1998 he became an actor—something he hadn’t attempted since he was a teenager. But performing his monologue Via Dolorosa proved a lot more difficult than he’d anticipated, and as a way of coping with the unfamiliar role, Hare kept a diary of the process: Acting Up. It’s an interesting read, not for the famous names he drops, but for the in depth way it explores the tension between the words you write on the page, and the words you speak in performance. What is the difference between acting and performance? And how do you play yourself?

I was re-reading Acting Up as part of preparation for F.R.G.S. A 10-minute Performance Essay for the PowerPoint Age, and my contribution to 7-ON’s The Seven Needs. A piece I wrote for myself to perform; a piece in which I play myself. F.R.G.S. is my second Performance Essay, but the first to be learnt by heart rather than read. For me, this act of memory was the source of greatest anxiety: Yeah, I might be word perfect in my living room and in rehearsal, but what if out there in front of an audience …

Forever ago in London I played the clarinet and saxophone in bands, cabaret groups and fringe theatre companies, but it was obvious to me—and it certainly was to anyone who heard me—that I was never going to be the next Lester Young. So I started writing to escape my limitations as a performer. Now on stage again (fortunately this time minus musical instrument), the experience proved terrifying and empowering in just about equal measure. My sympathy for actors has increased tenfold!

I hit on the idea of these Performance Essays for a couple of reasons. One: I’d always been interested in the traditions of the illustrated lecture and ‘slide night’, and having written some pieces for ABC Radio Eye which mashed documentary, the personal essay and performance, I was interested in adapting that genre for live theatre, and two: I was looking for a solo performance form that would work for me as a writer, i.e. it had to be cheap, portable, and involve absolutely no funding applications whatsoever.

More on this later. In the meantime, back to David Hare and the art of public speaking.

12 August 2007

Representation-lite

OK, here’s a view from Sydney on the STC: Yes, it certainly seems harder for a woman to get her foot in the door, even in the (relatively) small door of the variously-named Wharf 2 programs, where from Michael Gow in the early 1990s, to Brendan Cowell in 2007, the artistic directors have all been male. But why is the STC copping all the flack? Wasn’t it Belvoir Company B whose 2005 season included not a single female playwright or director? The perplexing thing there was that no one commented on this—at least not publicly. Does Company B’s strong record of supporting indigenous work buy them immunity from criticism on matters of gender?

Yes, women writers and directors are under-represented on our better-funded stages and over-represented in back rooms and pub basements. And many non-European performers struggle to get cast as anything other than gang members, refugees, and—for Asian actors—doctors. But I wonder how useful it is for us to keep chewing over this issue? Regurgitating essentially the same arguments? Plus ça change and all that. Perhaps in the words of Freedom, it’s time to ‘think outside the square’?

So here are a few thoughts:

· After a brief period in the spotlight, interest in inter-cultural work has waned. We still see overseas examples in festival programs, but for everyone here it seems it’s business as usual. Meaning artists from non-Anglo backgrounds get space to perform their own life-stories, but rarely a space to explore the questing, theatrically transformative agendas available to their White counterparts. (Why has interest in cross-cultural work declined? Would be interested to hear opinions about this … )

· It’s but a small step from representation to the heavy clay of identity politics, and escalating notions of ‘authenticity’. While I appreciate that autobiography and documentary are important genres in post-colonial societies, in that they are often the first places from which marginalised voices can speak and be heard … there’s a world beyond self-portraits.

· Is there really any point lobbying main-stage companies to represent our reality in anything other than a fairly tokenistic way, when they program for a conservative subscriber audience who, it seems, wants above all to see film and TV stars up close and personal? By all means send them your plays, and if they decide to produce them—fantastic. But if their door won’t budge, don’t waste too much energy trying to prise it open.

· Let’s remember that not all theatre writers and directors want to tailor their work and creative practices to fit main-stage imperatives. Sure, we’d like a share of their resources, but sometimes our artistic choices are better served in other contexts.

And finally—

Representation is too often posited as a destination rather than an ongoing process of engagement with the contemporary world. A destination reached through targeted initiatives and programs which can be rolled out like a carpet over any terrain, no matter how unsuitable or inhospitable. (I’m researching carpets at the moment, so they’re on my mind.)

Were these initiatives effective in the past? Maybe. To a degree. But the straight-talk about access and equality of opportunity that was once part of feminist, queer and post-colonial discourses of empowerment has given way as bureaucracies, universities and arts organisations have embraced the rhetoric. Today’s softer, more conciliatory calls for ‘representation’ have none of the rough edges of older demands for justice and transparency. So it should come as no surprise that what these well-meaning exercises produce is rarely any substantive or lasting engagement with diversity, but more often ‘representation-lite’.

03 August 2007

Part of Being Australian is Feeling Part of Somewhere Else

‘I once thought of teaching my son a private language, isolating him from the speaking world on purpose, lying to him from the moment of his birth so he would believe only in the language I gave him. And it would be a compassionate language … I wanted to take him by the hand and name everything he saw with words that would save him from the inevitable heartaches so that he wouldn’t be able to comprehend the existence of, for instance, war. Or that people kill, or that this red here is blood. It’s a kind of used-up idea, I know, but I love to imagine him crossing through life with an innocent trusting smile … the first truly enlightened child.’

That’s David Grossman, quoted in The Guardian, 16 August 2006. His son, who was in the Israeli army, had been killed a few days previously.

I’m not quite sure why, but Grossman’s plea, and the New Theatre’s resilience, both reminded me that a part of being an Australian is to feel a part of somewhere else.

26 July 2007

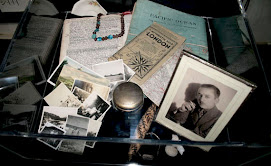

The Desk and the Dreaming Space ...

Pusan, 1999

Today I’m surrounded by skyscrapers. Simultaneously immersed in the Cold War theme park that is North Korea, and in the high art/high tech landscape of South Korea. On my desk are pages of notes on the history of concrete, a polythene-covered Penguin Classic, photos of the port city of Pusan, and my notebook from 1999—in which I wrote about an encounter with Chekhov on a winter evening in one of the city’s waterfront bars.

What am I doing? I’m working on UNREQUITED, a 30-minute Performance Essay for the PowerPoint Age which I’m presenting in Adelaide in September. No idea—yet—how I’m going to combine these various strands into a coherent whole. The piece is still in what I like to call its dreaming space: that exciting, early research stage, when curiosity is paramount, and you find yourself pursuing ideas and lines of thought for no apparent or discernable reason—just to see where they might lead …

So apropos of this meandering, here are my 3 favourite tenets from Bruce Mau’s An Incomplete Manifesto for Growth:

6. Capture accidents. The wrong answer is the right answer in search of a different question. Collect wrong answers as part of the process. Ask different questions.

8. Drift. Allow yourself to wander aimlessly. Explore adjacencies. Lack judgment.

9. Begin anywhere. John Cage tells us that not knowing where to begin is a common form of paralysis. His advice: begin anywhere.

15 July 2007

Factual Theatre—A Few Thoughts

‘A workable specimen of the kind of thin-sliced play that our theatres currently find most feasible, is not so much a text as a pretext. A slim excuse brings together 2 people with conflicting views, and their confrontation gives a handy opportunity for supplying information, exploring issues, and ping-ponging badinage till they both part, changed to varying degrees by their encounter.’

Unfortunately I didn’t note the reference, so apologies to its author. Anyway, I clipped it out because its sentiments struck a chord, and got me thinking about ‘journalism for the stage’. You know the template: On the one hand there’s Character—or Group—A, passionately committed to one point of view, on the other, Character or Group Z shouting the opposite. But what happens to theatricality when you make the stage the domain of rational debate?

Is metaphor suspect in our age of flux and insecurity? Ditto poetic imaginings and wild flights of dramaturgical fancy? What’s behind this hunger for factual theatre? ‘What these plays offer audiences is an open door into a subject whose density might otherwise be difficult to negotiate’, writes UK theatre critic Lyn Gardner in Does Verbatim Theatre Still Talk the Talk? True, but aren’t there other—perhaps more theatrically adventurous—ways of dramatising the material for audiences? Look at what playwrights like Caryl Churchill, Mac Wellman or Martin Crimp do—they take a topic and recompose it into an accumulation of fragments, glimpses, about-turns, and fraught, emotional encounters.

As I’m writing this however, I’m starting to wonder if my concern here isn’t thinness, rather than theatricality … the ‘thin-sliced play’. After all, I’m a huge admirer of David Hare’s Via Dolorosa, and Lawrence Wright’s My Trip to Al-Qaeda—although both of these sophisticated pieces are what I’d term ‘performance essays’ rather than plays.

I remember an article in The Sydney Morning Herald almost a year ago (29 August 2006) about verbatim theatre. One of the interviewed writers identified his problem with the genre: that often the characters don’t change significantly during the course of the play. My response: Does this matter if the audience experiences a journey? Or in the case of a community initiative, if the participants’ involvement is transformative?

Verbatim or not to verbatim … ?

I’m no expert here. My own experiments with verbatim are partial, to say the least. In REDHEADS (2007) I created a 1950s background for a contemporary drama, via the presence of 2 historical figures, General MacArthur and R. G. Menzies, who spoke a collage of their own words, all taken from documents on the public record. While the final scene of MRS PETROV’S SHOE (2006), in which we hear the insights and comments of a parade of fictional witnesses, is written in mock verbatim style.

Tragic, or at least serious, events seem verbatim’s strong inclination. Be they a tribunal, a small-town murder, or the demise and rebirth of a sporting team. (Are there any verbatim theatre scripts that are primarily comic? Or does comedy writing require a manufacturing or refinement of material incompatible with the verbatim ethos?) And in common with most classical tragedy, we usually have a pretty good idea of how the story ends. We know for example, that King Lear’s decision to divide his kingdom will result in disaster. That the incestuous Giovanni and Annabella in ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore, will die. Our interest is in seeing how these narratives unfold, and what resonances Shakespeare’s or John Ford’s way of telling arouses in us.

The verbatim approach, together with its close relative, storytellers’ theatre, both spring from oral history and community arts. I wonder if some of the criticisms now circulating about verbatim are a consequence of taking these works out of context and putting them onto mainstages at $40+ a pop? The productions I’ve seen have been heartfelt, hardworking, and deftly staged. They have revealed the triumphs of theatre that aspires to documentary status—and its key dilemma.

Do recent events, recent history, digitally translated for endless replay, restrict the possibilities for theatrical intervention? Limit metaphorical strategies, comic innovation, or poetic reworking? Maybe. Or at least they present a different challenge. We know the facts, can pull up images, sound-bytes, court transcripts, first-hand accounts, with the click of a mouse. So the task then for playwrights is: What can we add to, or do with, the facts to make the theatrical experience bigger and more meaningful than a montage of news clips or a magazine article?

12 July 2007

Have We Created a 'Prize' Model of Arts Funding?

The Sydney Theatre Company, when asked what it does to support new and local writing, invariably cites its Patrick White Playwrights’ Award—by far the largest cash reward for an unproduced play in Australia, but by no means the only contest for such scripts. Under the heading of ‘Fellowships’ Arts NSW runs an annual competition for historians, translators and writers. Glance at the ‘opportunities’ section of any writers’ organisation e-newsletter, and what you’ll see is essentially a list of competitions.

The accepted wisdom is that contests bring talented unknowns out of the woodwork. That’s the positive spin. The negative is that companies, broadcasters, producers and publishers get to tick the ‘new work’ box without having to pledge commitment. So my question is: Do these prize-orientated models serve the artists and artforms, or are they a way of managing scarcity? And I’m talking here about money to creators and interpreters to make new work, not dollars channelled into arts marketing and management. Take NSW, for example. Unlike most other states, NSW has no funding program for individual writers to generate new work. Instead they offer one—yes, that’s right, one—annual ‘Writer’s Fellowship’ open to playwrights, poets, essayists and novelists. When I’ve raised this with the relevant project officers, their explanation is that they put their literature dollars into writers’ centres and organisations, because that is the way to benefit the maximum number of writers. Hmm … not convinced. Aren’t you then supporting administrators, infrastructure, and promotional activities, rather than the actual writing?

Look, I imagine that initially these competitions were considered a bonus or supplement; one possible door into an overcrowded industry for newcomers. But I wonder if now these awards and ‘Fellowships’ with their attendant fanfare and publicity, aren’t in fact smokescreens? Helping disguise what seems like an ever-diminishing amount of arts funding (to creators and interpreters) in real and relative terms. I worry that when we replace ongoing support with one-off rewards, we are privileging the short-term over the longer term, fashion over longevity, a quick career-boost over genuine commitment. Ongoing funding allows theatre companies and individual writers to experiment, forge new processes, take risks, and develop projects whose scope and ambition may require many months, even years, of dedicated work.

I also wonder if the prize model doesn’t—subtly—encourage the view that writing is not real work which deserves to be remunerated, but a kind of lifestyle choice? A hobby to pursue in your spare time, when you get home from your ‘real’ job.

Then there’s the whole question of what kinds of work do prizes favour? Playwright Timothy Daley once said—can’t remember where, sorry—that comedies never win awards, and he’s pretty much on the money. You’re far more likely to make those shortlists if you tackle a topical social issue, preferably one which has been in the news headlines, and tackle it in a fairly straightforward form. Does this produce journalism for the stage? Hmm, this is a bit of a pet topic of mine, and I’ve got a lot of ideas about this whole vexed theatre/current affairs relationship, but I think I’ll leave that subject for the next post ...

26 May 2007

Redemption Sucks

I’m an early morning writer, and by midday or thereabouts I’m usually craving a break from whatever it is I’m working on. If I’m at home I’ll switch on the TV and eat lunch with Dr. Phil or Oprah. And a procession of unhappy or reformed guests looking to turn their lives around, or spruik their new tell-all book: How I Overcame Drugs/Abuse/Obesity/Obsession/Whatever. Oprah’s guests are frequently ‘celebrities’, while Dr. Phil’s tend to be Christian whitefolks. (You’d never guess the USA was the culturally diverse place it is from watching Dr. Phil.)

OK, so journeys from sin to redemption, adversity to success, are a popular theme in American culture. But where does this appetite for these kinds of narratives come from? Has it always existed, or is it a more recent hunger? Is it a by-product of the self-help and recovery movements? (See sociologist Frank Furedi’s article An emotional striptease in Spiked about the rise of ‘misery literature’.)

What I find particularly ironic however, is that although audiences and readers like the idea of redemption (and by extension, forgiveness) on stage, screen and in print, in reality we’re much less open and forgiving. And then there’s that murky political undercurrent … The right likes stories of redemption, because they validate their work-and-individual-responsibility agenda: If this person can pull herself or himself out of poverty or misfortune, then why the hell can’t everyone?

In a letter to his brother, John Keats introduced the wonderful concept of ‘negative capability’. We are, said the poet, ‘capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.’ I think my real problem with these narratives of redemption is their simplistic view of the world, their narrow notion of storytelling, their reductive, plot-point understanding of human behaviour and experience.

Perhaps I’m naïve or overly idealistic, but I believe that literature and art structure the collective experience; help us make sense of the world, stretch our horizons, and enable us to see ourselves in new ways. So if we’re going to have these tales of redemption—and their popularity doesn’t looks like waning any time soon—let’s go for the truly insightful and extraordinary. And top of the list I’m going to nominate St Augustine’s Confessions. One of the first autobiographies ever written, and a searching and disarmingly candid account of one man’s journey from a quagmire of crime, lust and hypocrisy to a new life in God.

10 May 2007

Paying the Writers—or not

According to the press release, selected writers will receive the following:

· return travel from their normal place of residence to Canberra.

· two weeks’ accommodation.

· daily meals or allowance as appropriate.

Yet again it seems the writers will not be paid. (Neither the ANPC nor Playworks paid the writers whose work they developed—don’t know about the state-based agencies.) Why won’t the selected playwrights be paid for their 2 weeks’ work in Canberra? Can anyone tell me the rationale for this decision?

Isn’t it a sad irony? We have an organisation ‘whose mission is to develop great new Australian writing for performance’ (that press release again) that chooses not to pay the very constituency it’s been set up to service and support. I presume the administrators, actors and directors will be paid for their 2 weeks in the ACT? I appreciate that funds are limited, but still …

On a more cheerful note, credit where credit’s due. Some development programs do pay writers. Breakout at Parramatta Riverside Theatres in Sydney, for example. So come on PlayWriting Australia, you’re a new organisation—what better time to chuck out old, unfair practices and start afresh?

+Photo+Leah+McGirr+3.jpg)